Forget Programmatic Commerce; Assortment is Still King

There’s been a lot of talk about “programmatic commerce” recently; basically commerce involving machines that anticipate what you need automatically without you having to seek products out (think automatically ordering more coffee because you’re running low).

Add it to the endless list of “cool ideas for the future in retail that we won’t see for years”. Today’s retailers are still hustling to compete at a much more basic level.

The major cultural trend in the US is the death of the blockbuster, mass market, and the growth of niches. When I was growing up, jeans were Levis. Today, there are 1000 brands.

The shift from “everyone shops at the mall” to “there are a billion places to shop and most of them have the same things” has ended, and now we’re in a phase where, increasingly, all the stores don’t have the same things anymore. Over the last couple years this trend of differentiating on interesting assortment vs. just amount of assortment has accelerated (see Amazon’s latest move into pushing their own fast fashion brands).

There are many ways for retailers to differentiate based on assortment which are really interesting, and I want to explore a few here.

Lululemon & Growing a Tribe

Lululemon’s meteoric rise was due to having a highly differentiated product assortment. Their athletic gear is stylish and high quality, but even more importantly, people who shop at Lululemon (my wife among them!) identify with the lifestyle and values that Lululemon espouses. For example, every store has a wall of employee pictures where they describe their dreams and goals.

Having a smaller assortment comprised mostly of own brand products is a strategy employed successfully by many others like Bonobos, Warby Parker, and stalwarts like LL Bean. As with Lululemon, in all of these examples their customers aren’t just buying into the product quality, they are, to an extent, buying into a whole lifestyle. Each store has a distinct image that helps with customer loyalty, something that big box stores - including Amazon - could never deliver.

That is, the success of brands like Lululemon isn’t just a product success, it’s a success in building a loyal tribe around a shared group image.

These days it’s not enough to simply develop one cool product, or even a series of products - they have to mean something to people. If you get that right, you’ll have loyal customers that pay above-market-price and come back again and again.

The Netflix Strategy for the Majors

But what if you’re a big box retailer with millions of products on your virtual shelves?

Netflix has tons of movies, but it’s driving growth and loyalty based on its own award winning programming like House of Cards. This is similar to the Lululemon strategy, except that 99% of Netflix offerings are others’ products; they’re using their own 1% to drive growth and loyalty.

Similarly, the major retailers are developing private label brands more than ever. Target for years has had own brands like Merona, and Amazon has been expanding its own brands in many categories such as Amazon Basics in electronics and Society New York in apparel. JC Penney is creating a new of plus size clothing for women.

These products drive margin, but they don’t (yet) have the Netflix appeal.

Put it this way: I might buy a Merona because I’m in a Target, but I wouldn’t (today) go to Target to buy a Merona.

Time will tell whether the big box stores with huge assortments can create lasting and differentiated product brands to bring people into the stores in the first place and keep them coming back.

Huckberry: The Innovator

Huckberry is one of my personal favorite sites to shop at. It’s got this awesome “mountain man chic” image. Unlike Lululemon, they make very few of their own products; instead they market interesting and unique products that match their image.

I open every single email Huckberry sends me. They are filled with articles and cool things that I didn’t know existed, and wouldn’t know to search for. Going to their website is an experience because the vast majority of the brands are not household names, and so it’s interesting. It’s a much better place to buy great things for me, or gifts for my wife, than other stores because their assortment is painstakingly differentiated.

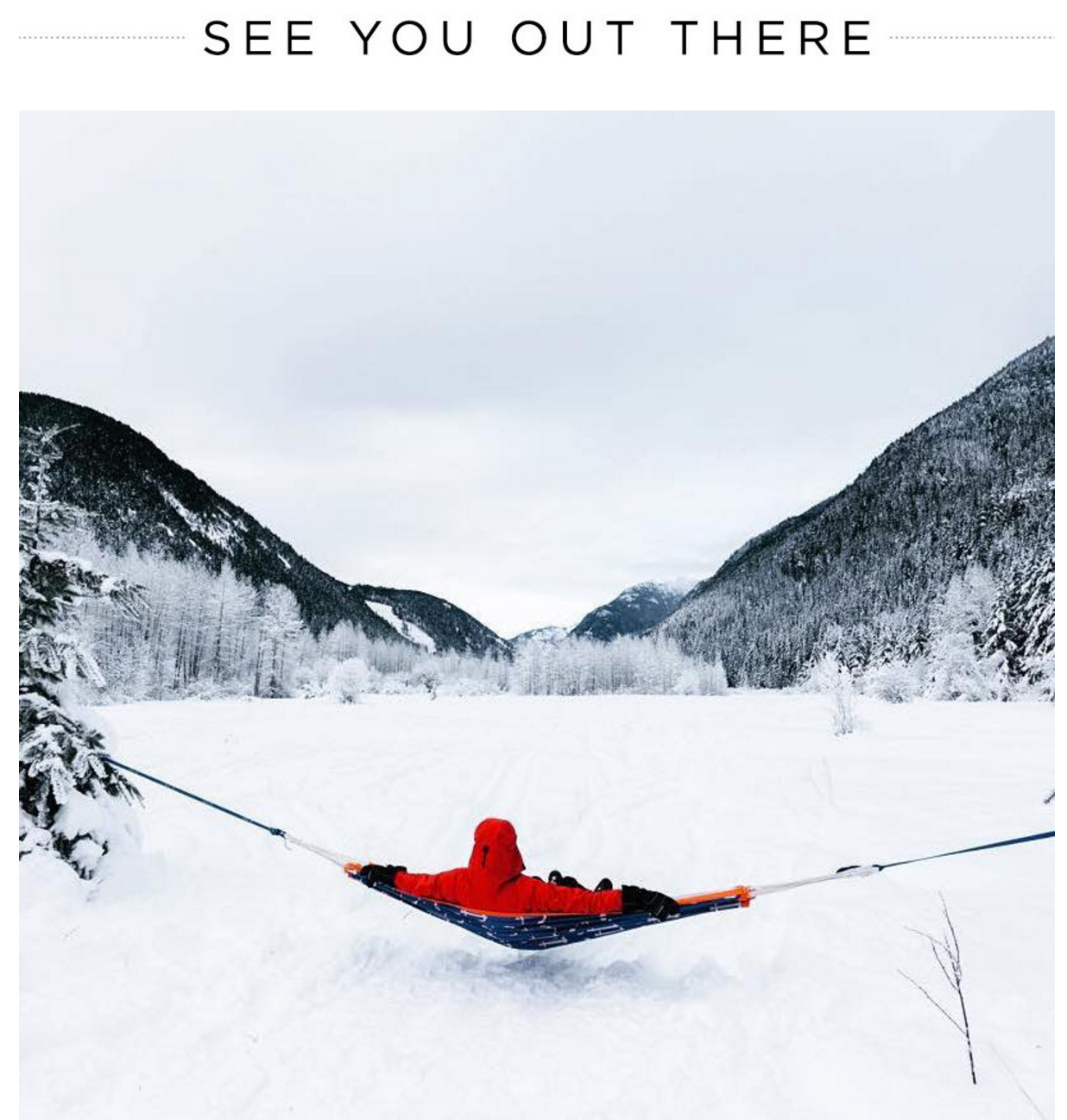

Huckberry ends every Newsletter with a “see you out there” pic. I always want to go to there.

Huckberry ends every Newsletter with a “see you out there” pic. I always want to go to there.

I spent years working at Endeca, which powered the search & navigation of more than half of the Internet Retailer top 100 sites (e.g. Walmart, Target, Home Depot, and others). The challenge was always figuring how to build a browser experience online that helped customers discover new products that they didn’t know existed among hundreds of thousands of products on a site. It’s a really, really hard problem to solve well.

In contrast, Huckberry has a relatively crappy search and navigation experience. But they don’t need one, because the entire site is built to browse.

I really think there’s something to the Huckberry strategy of a very tightly managed assortment of high quality products that other retailers can learn from. Most correspondence - email or otherwise - I get from any big, serious business focuses on what’s on sale; it’s all about them. Huckberry actually gets me excited about what they’ve got because they’re excited about what they’ve got. It’s not just about moving units, it’s about sharing something.

Why couldn’t Home Depot, for example, have a monthly newsletter for DIYers that order tools and other home improvement with tips and tricks, or with stories of cool renovations? Sure you could link to a product here or there, but it might help with engagement. This content could be posted online more aggressively, driving top-of-funnel customer acquisition with “how to” searches on Google. Of course, that’s exactly where they’re heading, because it adds value to their customers and drives loyalty.

Where to from Here

This shift in the market has been fascinating to watch. My guess is that there is going to be increasing fragmentation and increasing growth of lifestyle brands, and that the major retailers will see great margin benefits but not as much loyalty benefit from development their own brand products until they embrace other aspects of the “own brand” strategy that go along with it.

gonzofy

gonzofy